Remembrance of an American life

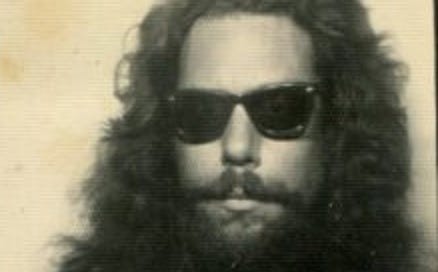

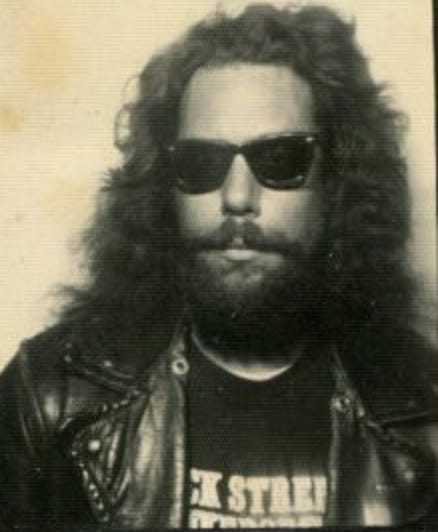

The one and only Chris Pfouts, that would be: raconteur, gifted writer, a bon vivant’s bon vivant, and a very close, very dear friend to me. From one of the best of many Pfouts obits still extant out there:

CHRIS PFOUTS REMEMBERED

(“I Knew Right Away He Was Not Ordinary”)In 1986 a mutual freelance-writing friend had invited each of us with many others to his annual Easter gathering at his New York home, and that’s where I met Chris—a versatile, merrily opinionated fellow scribbler who was the picture of the biker gang-leader you’d never want to meet in a dark alley: he must have been 6-foot-five from the long thick hair down his shoulders to his motorcycle boots, with a broad lean build of California surfer steel, a quick bright smile and piercing stare, a goatee gracing his rough rocky features, and always a beer in his formidable mitt.

Chris loved to laugh, especially right through anybody’s pompous pretensions. He loved rough ruthless honesty, and he knew how to listen before he drove his wit through your brain, gut, or both. While I was writing for educational textbook publishers, Chris wrote for and edited various motorbike and tattoo magazines: two of his primary passions, not to mention his love for hard-hitting literature, hand-crafting jewelry, and his ever-growing collection of vintage children’s toys, most lately including a “Mr. Machine” fresh out of the 1960s box, whose acquisition tickled him like a giant kid. Before the day was out, we each knew that the other was struggling to write our first serious books, and we made a pact to swap manuscripts and feedback. Having noticed that Chris came to this half-dressy holiday gathering in jeans and a T-shirt, it was too late to escape the pact when I saw at last the “Psychotic Reaction” tattoo on his bicep.

Plowing my way through the ancient-world research for a literary historical novel, these first impressions made me dread Chris’ sometimes-brutal bluntness—and yet I wanted to know if the work could stand up to it, and if I could rise to his comments and his friendship. In fact, Chris went into thoughtful, open-minded detail far beyond anybody else’s reactions, he told me plainly what he thought I should hammer harder and what I should drop, and I daresay the work gained tremendously from his response.

As a matter of honest fact, I was always surprised by and glad to see that Chris actually enjoyed our hanging out—for of course whatever Chris wasn’t enjoying never lasted long on his dime. His various New York apartments were big quasi-industrial spaces where he could spread out his projects and passions: he loved all kinds of exotic mechanical junk, rare crazy records, and always there was a half-assembled motorcycle splayed out in his living-space, his dream to build/restore for himself the perfect vintage Indian Chief.

As it turns out, I helped Pfouts put the finishing touches on that Chief after he’d moved here to CLT and we’d both departed NYC for good, and a wonder to behold it truly was: unique; captivating; so out-there as to even be bizarre in spots—as honest and true a reflection of the man behind the machine as I’d ever had the privilege to behold in decades of wrenching professionally on American-made motorcycles.

Then, by the fall of 1987, I got the lifetime-opportunity to leave New York for the Greek island of Crete (about which I was writing), and Chris’ letters kept his usual sparks flying as he bounced from gig to gig, writing constantly in multiple modes and, like me, fighting for that break that could launch the life we really wanted—answerable to nothing except our skills and arts.

When I came back from that dreamlike year of writing by the sea in Crete, I bounced next for a year to Portland, Oregon, where my engagement with a terrific woman broke up on the rocks of my virtual unemployment; and, not wanting to live in New York anymore, I next bounced back to my family home north of Boston, while Chris left the city for new freelance horizons in Pennsylvania. His letters said he found it as drab and dull there as a rusty muffler, and eventually he returned to New York City. Soon I’d bounced again, back to Crete on my own for another year of trying to finish that goddam novel and land a European publisher for it—and Chris, to my great surprise and pleasure, came over to see what this Greece thing was all about for two weeks in that May of 1991.

He had meanwhile sent me the much-appreciated company of some of his favorite half-whacked tunes collected on cassette: it opened and ended with “Hot Rod Lincoln” versions by Johnny Bond and Commander Cody. The rest of the list was pure Chris-company that kept my isolated spirits up: “Out With The Girls” and “Fujiyama Mama” by Pearl Harbour, “Six Days On The Road” by Dave Dudley, “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door” (by “Dylan Is God”), Captain Beefheart’s “Plastic Factory,” “Baby Please Don’t Go” by Them, “Big Balls” by AC/DC, three Black Sabbath tunes (“Ozzie Fuckin’ Rules!”), and the creepy-funny “Transfusion” by Nervous Norvus.

None of those tourist-pussy Vespa’s for Chris: he was going to ride a decent bike or forget it, and I deferred to become his rider as we took to Crete’s seacoast and mountain roads, with him driving and me guiding the tour. Chris instantly loved the island’s semi-desert high country and bright blue sea, the fresh food and warm-hearted people, the blasé way in which everyone enjoyed the almost-naked beach customs and topless sunbathing European nymphs. Chris couldn’t stop often enough to photograph the new-to-him language of Greek highway signs: for example, a simple exclamation-mark before a hairy turn or hazard which he translated roughly, “Hey stupid, wake the fuck up!” He also loved the little roadside shrines that usually marked where somebody had been killed by careless driving: more than once it was nothing but Chris’ sharp eyes that saved us from plummeting down into some hairpin-turn’s ravine or into a road-collapsed pot-hole. “Oh, look!” he’d say pointing at one with his best Curly-voice from The Three Stooges. Chris was also rich with always-spot-on lines from books and songs for every occasion: talking about a certain slim romantic hope of the day, he laughed with Dylan, “I still can’t remember all the best things she said!”

As we stopped someplace to swim and eat, I saw for the first time Chris with his shirt off, and almost fell over when I saw the ultimate writer’s tattoo across the huge expanse of his back: he’d never mentioned having it, but there was the biggest and most detailed image I’d ever seen on a human body, a shapely brunette in leopard-skin bra and tights leaning back on an old Remington typewriter whose rendering made you think you could tap the keys. And that, baby, was Chris’ muse: the woman who’d never get off his back.

Yep, I well remember that amazing back-piece (a pic of it is included in the obit). Brigitte Bardot, that’s who the leopard-clad pinup chick recumbent on that old Remington typer was intended to be, he told me.

There was also a kind of new caution in Chris, who was now holding off from more than a couple of the Greek and German beers he liked so much, and the explanation for that also came from his flesh. Chris had been shot, in the leg, one night during his last year in New York, and the scars from the hell-hole hospital operations he’d endured to save it were horrifying. His manly reticence meant I’d never heard about it, and would get no real details until he published Lead Poisoning: 25 True Stories from the Wrong End of a Gun later that year. But I do know that he came through it not only thinner and more cautious, but more subdued, having looked—as he’d almost bled to death on that Brooklyn street, shot by a neighborhood crack-dealer—into the face of the real Reaper.

The essential facts: one summer night, living in his usual big-and-cheap-rent kind of place in Brooklyn, Chris stepped out across the street to the local bodega for some beers. He’d casually dropped his latest bag of trash into a curbside can, and as he then stood waiting in line in front of the bodega’s bulletproof window, he watched a local young crack-dealer rip his trash-bag out of the can, come across the street with it, and pour its contents all over the street in front of him. “Yeah?” Chris shrugged to him. “What are you gonna do now?” The reply was, “I’m gonna do this, motherfucker,” and the shit-for-brains pulled a pistol and shot Chris in the leg. Chris, by chance having dropped his trash on top of the dealer’s street-side dope-stash, went down, then managed to crawl as he bled back up the stairs to his apartment, and had the terrified presence of mind to call a friend before he dialed 911—so that, in case he went into shock, he could be sure that his Emergency call wasn’t a delusion that left him to bleed to death. Chris only just barely survived at all, and several restorative surgeries put him through a god-awful gauntlet of the medical care that mostly-impecunious Americans typically receive.

I remember that nightmare episode also; I’d become close friends with him well before that, the near-fatal shooting occurring shortly after he’d fled his old Suffolk Street pad in Manhattan to move out to Williamsburg. This was before W-Burg had been gentrified from a horrid, dangerous slum into the yuppie-puppy play-park it remains to this day. For his part, Pfouts turned his blood-drenched ordeal into a book, Lead Poisoning: 25 True Stories from the Wrong End of a Gun. He wanted to put me in the thing too, but having managed to avoid being shot (to that point in my life, at least), I was forced by circumstances to be omitted. Thankfully.

I've written about Pfouts at the CF mothership before; the guy had a huge impact on everybody who was fortunate enough to meet and get to know him. He was NOT the kind of man you can easily forget, not by a long yard he wasn’t. With True American Originals, that usually turns out to be the case.